Like what seems to be the bulk of the internet this past weekend, I watched Hamilton on Disney+. And, as will come as a surprise to precisely no one who has ever met me in real life, my husband and I then spent much longer than is healthy picking apart the history behind the play. Now, first things first, I am a fan of the musical. I bought the soundtrack back in 2015 and memorized it all. I spent way too much to go see the performance at the Kennedy Center when it was in D.C. Nitpicking the history wasn’t at all about trying to tear the play down, it was about analyzing the creative choices. There is no doubt that Lin Manuel Miranda is familiar with his topic. Like most (if not all) historical fiction writers, he fully immersed himself in his era (even getting to write at one of Hamilton’s desks at a historical site in New York—proving that there are perks to being a famous writer over the rest of us doing the bulk of our research through commercially published works and whatever we can Google/find online).

By PBS, “Hamilton’s America” screenshot

Since history does not often conform itself to a perfect narrative, however, the fiction part of historical fiction sometimes does take necessity and leads to little (or sometimes big) cheats to tell the story you’re trying to tell. And so, Hamilton becomes a great example of how things sometimes have to give when you’re digging a great historical fiction out actual history.

For example:

Timelines get compressed (or changed entirely):

One of the cardinal pieces of writing advice often given in writing classes is “if it doesn’t serve a purpose, cut it.” When it comes to telling a story, every scene should be propelling your narrative and characters, be that providing new information, taking the characters closer to (or farther from) their goal, or building characterization. Unfortunately, history generally isn’t kind enough to do the same. Especially in the past, things took time to happen. There were weeks between letters being sent and delivered, people would go home to plant their fields before eventually returning to finish whatever “more important” action they started months ago… all in all, a bunch of “actual life” stuff gets in the way of a narrative arc. For that reason, historical fiction often trims the time it takes between events or sometimes even rearranges when specific events happen. The play Hamilton has a bit of a leg up in messing with the timeline in that it can paint with a very broad brush with time passing (when exactly did Hamilton get this letter? Well, it’s sometime between the Battle of Yorktown (1781) and the Constitutional Convention (1787)… pick a time) but even with that, it is still possible to pick out places where the timeline has been rearranged for storytelling.

twinkl.com

A good example of this is the song Farmer Refuted. For this song, Miranda uses a common historical fiction “trick” where he takes writing from the actual historical record and then translates it into action on the stage/page. Unsurprisingly, Samuel Seabury did write an actual “Free Thoughts on the Proceedings of the Continental Congress”, from which his lines in the song are taken. Hamilton then wrote a response (two, in fact, since the play is correct in that he was never one for moderation in his writing) which he titled (any guesses?) “The Farmer Refuted”. I particularly like this example as it encapsulates both compressing the timeline and rearranging it. As these were pamphlets and responses written back and forth, obviously there was a lot more time necessary for this exchange than the few minutes shown on the stage where Hamilton literally steps onto Seabury’s soapbox and talks over him. These pamphlets were also written in 1774 and 1775 respectively, placing them solidly before the “1776, New York City” time and place setting given in Aaron Burr, Sir, which is five songs ahead of Farmer Refuted in the play. Since the entire narrative point of Farmer Refuted, though, is to show Hamliton’s bombastic approach to speaking his beliefs (setting up the dichotomy between him and his foil, Burr) and progress the story toward the actual fighting of the revolution, Miranda took these earlier works and transposed them into a single exchange that makes his intended point in a narratively interesting way that the actual timing would not have allowed for.

Similarly, events are rearranged to fit in (spoilers for actual history?) Philip Hamilton’s death. In actual history, Philip Hamilton died in 1801. Fans of the musical will recognize this date as decidedly after the Election of 1800, which in the play happens in its eponymous song two tracks after Philip’s death in Stay Alive (reprise). This change was narratively necessary, however, as Miranda further compressed the narrative toward the end to remove a lot of the other events that led up to the Hamliton/Burr duel. In actual history, this duel is more closely connected to Burr’s New York gubernatorial campaign than his presidential campaign (which is also the reason Hamliton’s death is in 1804, rather than closer to 1800). Since the condensed narrative for the play would not support dealing with the conflict between Burr, Hamilton, and Jefferson in The Election of 1800 only to then have Philip die and then there be another conflict around an election, Miranda made the decision to move Philip’s death forward to then allow the Election of 1800 to serve the narrative function of both conflicts between our protagonist and antagonist. While in longer works of fiction, such as novels, readers perhaps might not allow quite as broad of changes to be made unremarked, as there is more time to get into nuances, in a time-compressed play or movie especially, joining these events to serve one singular narrative beat that leads to the historically accurate outcome is understandable.

Characters become symbolic:

While watching the Disney+ broadcast, one of the topics that we kept circling back to was Daveed Diggs’s portrayal of Thomas Jefferson. While Diggs does an amazing job with his physicality and character choices (he’s actually one of my favorite performances in the show) the person he is portraying is decidedly not the reserved, almost comically introverted, by many accounts, Thomas Jefferson. Rather than attempting to write an accurate Thomas Jefferson, Miranda wrote a character meant to be the embodiment of Jeffersonian ideas. He needed a quick, engaging way to show the conflicts between the Democratic-Republicans and Federalists in the early Federalist Period, and an accurate, reserved Jefferson would not have been able to match the bombastic energy of Hamilton’s character. Realism was thus once again sacrificed so that the narratively necessary points could be made. While in fiction it is always necessary to have characters feel realistic enough to be engaging as people, when telling a greater historical narrative, characters do often also fall into a symbolic role as well. One character may be a down-on-his-luck tailor but he is also the symbolic “put-upon proletariat” character the reader needs to connect to to get the full impact of the coming revolution or another character may be a charming poet, but she is also the mouthpiece for Romantic Era ideals to be able to show how the world is changing. In this way, Miranda has turned Diggs’s Jefferson into a charismatic symbol of conflicting political ideals rather than gone for anything close to a realistic portrayal of historic Thomas Jefferson.

Similarly, to serve the romantic subplot of the show, the Angelica Schuyler Miranda has written is a far cry from her historical counterpart. Miranda is on record as saying that he felt Hamilton needed an intellectual equal as a love interest, and thus developed this bittersweet “soulmates who can’t be” relationship between Angelica and Hamilton. Beyond the plainly “factual” errors that building this plot required (Philip Schuyler had eight children, including three sons despite Angelica’s line in Satisfied stating, “My father has no sons so/I’m the one who has to social climb for one”) Miranda also builds a character who is a mental match for his version of Hamilton by giving them a shared dissatisfaction with their lots in life. Unlike other women in the era who were proto-feminists (most notably being perhaps Abigail Adams in her 1776 letter urging her husband to “remember the ladies”) there does not seem to be any real evidence in the historical record that Angelica Schuyler shared the sentiment or would have tried to “compel [Jefferson] to include women in the sequel” of the Declaration of Independence’s “all men are created equal”. Rather than being a historically accurate Angelica who, while definitely witty and period-appropriately flirty in some letters, was already married by the time she met Hamilton and seemingly satisfied enough with her life, she becomes the character necessary to build a love triangle for Miranda’s Hamilton.

Language changes:

neh.gov

With Hamilton being a rap musical, it is hardly surprising that the language used in it is not period accurate (you mean to tell me not only were the Schuyler sisters not a trio of feminists, but they also wouldn’t have said “Work!”?) but this is something that all historical fiction authors come up against. For any book set before the 18th century, it is more or less understood that the piece of fiction the reader or viewer is digesting is a “translation” much in the same way that a fantasy novel is a “translation” from whatever language would be spoken in that fantasy world. Historical fiction readers/viewers don’t expect to pick up a book set in the middle ages and find something written in Old or Middle English. Similarly, there is a certain level of “suspension of disbelief” with any novel that needs to use more modern equivalents of difficult historical phrases to be understood. Obviously, just like with plays getting more ability to compress events in general, Hamilton gets an extra level of suspension of disbelief with its language than “normal” historical fiction due to it form. However, it also treds that line all historical fiction does of providing a “realistic” experience (including actual lines from “The Farmer Refuted” (Farmer Refuted) “Washington’s Farewell Address” (One Last Time) “The Reynolds Pamphlet” (The Reynolds Pamphlet) and Hamilton and Burr’s letters (Your Obedient Servant)) while also remaining accessible to modern audiences. Much like writing that medieval novel in modern English, Miranda manages to translate moments in history using non-accurate language by finding modern “equivalents”, such as a rap battle rather than an early Federalist cabinet debate, much in the same way that a novelist might need to use the slightly less period-appropriate word “science” instead of “natural philosophy” in a throwaway line of dialogue for it to be easily digestible. Obviously, all historical fiction authors need to know where exactly the line is for their own suspension of disbelief and work to keep their “translations” grounded enough to their own internal logic to not lose readers, but as we can see, if the changes are done well, they can do an amazing job of getting people who have never been interested in a period (or perhaps history in general) hungry in finding out more, and that truly is one of the wonderful things Hamilton has managed to do.

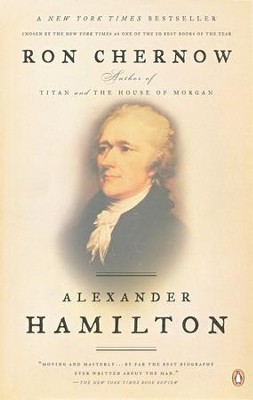

For those who are interested in the actual history of these characters and events, I strongly suggest picking up some non-fiction, such as Ron Chernow’s Hamilton, which gave Miranda his idea for the show to start with and seeing for yourself what the musical Hamilton does and doesn’t change. For those who are interested in writing historical fiction, I strongly suggest doing so as well, even if it’s just to be able to fully dissect what Miranda decided to keep and what he decided to change to build a tight, engaging narrative. I will not attempt to argue that every choice was perfect or if he should or shouldn’t have used such broad strokes in places (there are many pieces out there that have done much more justice to those arguments than I could in this short blog post), but if you—like I previously have—are currently caught up trying to balance history with fiction, this musical truly is a great study to at least get your feet wet with what changes may or may not work in your own narratives.

Interested in more historical fiction? The Stars of Heaven available August 18th, 2020.